Who were the Scythians?

The Scythians were originally tribes of nomadic warriors who roamed the land known to us as Southern Siberia. In the fifth century BC, Herodotus wrote of monuments showing that the Scythians were related to the Cimmerians, an older culture of the ancient steppe. Many tribes shared the same economic and cultural existence over a very wide area. By 200 BC Scythian culture had been flourishing for three hundred years and their influence spread from China to the Black Sea, where, on northern coastal flatlands, the Scythians buried their dead in earth burial mounds called ‘kurgans’.

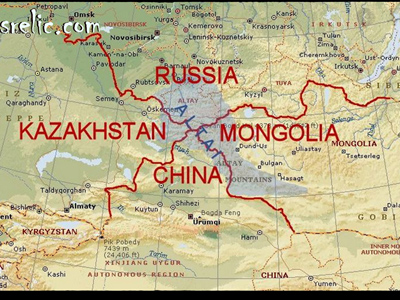

From the sixth to the third centuries BC, the Scythians occupied the steppes between the Don, the Volga and the Urals, their culture linked tribes of Eastern Kazakhstan and the High Altai.

Culturally, the Scythians were regarded as excessive drinkers, who did not water down their wine like the Greeks. Heredotus observed Scythian ‘vapour baths’ where, inside a tent, hemp seeds smouldered in order to intoxicate the occupants. Living in prototype caravans, their lifestyle required little furniture, although they appreciated a good carpet.

The Altai mountain region forms the border for Russia, Kazakhstan, China and Mongolia and it is here, in these mountains that Scythian burial tombs have been discovered, preserved in the permafrost. The tomb chamber is typically a wooden room built at the bottom of a deep hole. The mummified body rested in a tree trunk coffin surrounded by possessions. Their well preserved grave-goods show fine artistic development. Sacrificed horses have been found outside the tomb chamber but still within the grave shaft, facing east.

Scythian warrior society had no interest in writing, but developed weapons, using a powerful, superior bow used in warfare. Mounted archers achieved the complete destruction of their enemies and in the fifth century BC the Scythians had the capacity to sack Nineveh, Assyria’s main city.

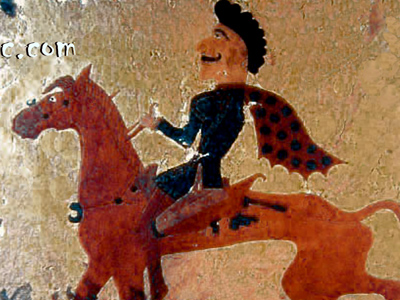

The Scythians learned about horses and improved their riding skills on the grassy steppes of Siberia, covering vast distances from Mongolia to the Black Sea as they managed large herds of sheep and cattle. Horses wore festive head-dress, they were also sometimes sacrificed as part of a warrior’s grave goods. A chieftain’s gold torque discovered in a Crimean grave and dated to fourth century BC depicts a bearded horseman, wearing an ankle length caftan tied at the waist, with long trousers held by a strap beneath the boot. The horse had a harness and bridle, but was ridden bare-back without stirrups.(Gold pectoral of a Scythian king from the Tovsta Monyla burial mound (near the city of Pokrov), 1.14kg, 4th century BC).

Scythian Art

Scythians art can be seen from textile decoration to rock art. Craftsmen excelled at metal work, utilizing Siberia’s rich metal ores. Techniques included casting, forging, and inlaying, and they worked gold, bronze and iron. (SCYTHIAN WORLD by Boris B. Piotrovsky, Soviet archaeologist)

Scythian art is notable for specific motifs such as the reclining deer ,and it absorbed ancient Eastern imagery such as the holy tree with it’s attendant divinities and fantastic animals.

In 1830, on the straits connecting the Black Sea to the Sea of Azov, a stone vault was uncovered beneath a fourth century BC burial mound. It contained Greek-made jewellery that used Scythian motifs. Included were figures illustrating a Greek legend about the founding of the Scythian dynasty. A short Scythian dagger was found in a burial mound excavated in 1763. It’s scabbard and hilt was decorated with fantastic animals and ‘anthropomorphic deities’, gathered around a sacred tree. Artefacts such as horse gear, iron weapons and beads, were found in Scythian burials of the Black Sea region, and similar have been discovered in Armenia and ancient Urartu. Further, a seventh century BC tomb containing the “Ziwiyeh treasure” was located in Iranian Kurdistan, with Scythian burials in the Ukraine yielding a number of Thracian objects.

Kurgans, from the coastal steppes to the Kuban region, all reveal magnificent Scythian art and it has been suggested that the reclining deer with branch-like antlers and the panther MAY have been tribal symbols.

In the words of the Soviet archaeologist, Aleksandr Shkurko, an authority on early Scythian art,

“The artist was not unduly concerned with modelling the animal’s body or adding precise detail.

What held his attention was its inner qualities : its strength, speed and essential wildness. The decorative treatment of the horns and the compactness of the composition confer on the image an almost heraldic appearance.”

Tattoos

Bodies discovered in Scythian burial tombs are extensively tattooed. Designs include fantastic animals, birds and dots perhaps suggesting a system that used acupuncture.

A tomb discovered in Pazyriyk in the Altai mountains of Siberia held the oldest known pile carpet yet discovered and with it were five heavily tattooed individuals.

The site, high in the remote Siberian Ulagan Valley was first excavated in 1929 by two scholars from Leningrad. They returned in 1947-49, discovering perishable artefacts, frozen and preserved for almost two and a half thousand years. The mummified bodies of men and women were found with a ceremonial chariot and horses in rich trappings.

One elderly Pazyryk chieftain was embalmed, his skin portraying a lifetime of intricate tattoos. Beasts, real and imaginary, pranced and tumbled down his arms and other parts of his body. The frost preserved the designs which were made with soot rubbed into pin pricks made into the skin. Designs are shown in the book, “Frozen Tombs of Siberia” by Sergei I. Rudenko ©J.M. Dentand Sons, London1970

More tattoos were found on a mummy that became known as the Siberian Ice Maiden.

Also recovered from a Pazyryk grave, this Iron Age woman was discovered in 1993 on a plateau in the Ukok Mountains, in the modern Republic Of Altay. Dressed in expensive Chinese silk, she probably died around the age of twenty five. cancerIt is assumed that she was a shaman or from a high ranking family, and that this is reflected in the design of her tattoos.

Her tattoos, from her shoulders down to her hands, are assumed to indicate a certain social status, and maybe denote which tribe she belonged to. It is suggested that the animals represent the living and the after-world. A mythological animal on her arm represents a deer with griffon’s beak and goat antlers, a panther with sheep’s legs and a deer’s head. Two warriors buried nearby had tattoos that matched. It is believed that a person always had their first tattoo on their shoulder, usually the left one. The number of tattoos could have been linked to age, as older people had more. The Siberian Ice Maiden has among the most complex tattoos discovered on a body dating from this period.

The Siberian Ice Maiden is now kept in a Mausoleum at the Republican National Museum in Gorno-Altajsk, the Republic of Altai.

“Art was indeed in the people’s blood. And the images of animals and birds, whether wild or domesticated, real or fantastic, which figured in their decorations were more than brightly coloured ornaments. They revealed the spirit of the people, their beliefs, the way they looked at things. In their travels abroad, the ancient Altaians absorbed what was best in their neighbours’ art, and then added their own local colour and interpretations. Thus, they found place in their own creations for griffins and sphinxes borrowed from Western Asia, and for patterns of lotus flowers, ornamental palm-trees and geometrical designs whose origins were in the countries of the near East and in Egypt” Mariya P Zavitukhina

The Scythians were superseded by the Sarmatians by 200 BC who became known to Greek trading colonies along the coast north of the Black Sea. At their peak in the 1st century AD, Sarmatia, the Sarmatians territory, corresponded to western greater Scythia.

This information gathered from article :

The Scythians: nomad goldsmiths of the open steppes, The Unesco Courier

https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000074829https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000074829